As I’m finding out: many things change, while other things stay the same. My compositional output of art music scores has changed quite a bit in the past few years, yet, I still see similarities between the newer and older. 2018 was a particularly busy year, chiseling away at new discoveries and synthesizing new ideas into my compositional outlook. The results have been amazing and interesting.

However, I have been approached with many questions regarding some of my newer works: “what is the intention, here?” or “how are these figures and passages to be played?”. So, I thought I’d take the time to give a little, basic primer post into my view of marrying modularity and asemics into my latest performative art scores.

What is Modularity?

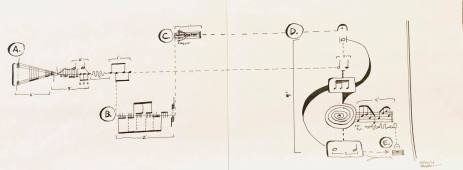

A good primer on modularity in musical composition is James Saunders’ article “Modular Music” in Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 46 No. 1. The article’s language is easily accessible, and he makes connections to many other modular applications that we use everyday (such as modular IKEA furniture and the popular Danish toy, Legos). To summarize the subject: modular musical compositions are pieces of music that contain independent sections that are made performatively interdependent either via instructions (or ‘interface’, as Saunders’ puts it) or through performers’ intuition. This means the performances of each piece will be different to the audiences ear, while the raw pieces of musical information penned by the composer stays the same on the score. The overall goal of most modular (or mobile) compositions is to build a musical architecture by putting these malleable puzzle pieces (modules) together in interesting ways.

While studying modularity in the works of Manuel Enriquez (Móvil II for solo piano, 4×4 for solo piano, and others) in late 2016, I became fascinated with the overall process of performative exploration and collaboration (with self or others), and how that process might affect the overall result of the musical architecture.

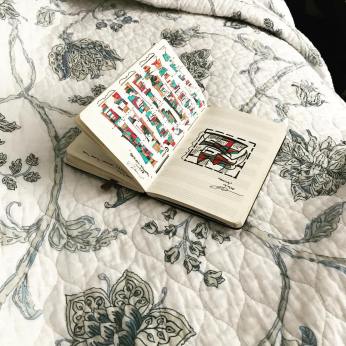

I started writing several pieces with, both, closed (the interface creates limited numbers of combinations) and open (the lack of interface creates virtually unlimited combinations) modularity: Shelter for solo piano (2016), ink constellations (2016), reflection now: I (2017), untitled contraption no. 1 and no. 2 (2018), thought/nexus (2018), 10.3 for orchestra (2018), and many others.

Asemics

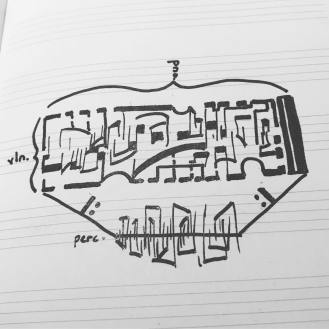

The path that the modular composition process has taken me has been an interesting one. Each new work seems to progress in some areas, then – on the other hand – reuses similar vocabulary and shapes from other works in other areas. Even the musical and symbolic gestures within the aforementioned works became much more open and interpretive over the course of their completion; geometric shapes, lines, noteheads – all becoming broken and resequenced into larger forms for performing musicians to study and put back together. Before I knew it, I was writing music that contained many musical (and unmusical) symbolic gestures that were highly interpretive. Once that line was crossed, my output became more asemically based by using the visual forms that are found in traditional musical notation in a very different way. According to Minneapolis-based visual artist/writer Michael Jacobsen:

The forms that asemic writing may take are many, but its main trait is its resemblance to ‘traditional’ writing—with the distinction of its abandonment of specific semantics, syntax, and communication. Asemic writing offers meaning by way of aesthetic intuition, and not by verbal expression. It often appears as abstract calligraphy, or as a drawing which resembles writing but avoids words, or if it does have words, the words are generally damaged beyond the point of legibility.

History has recorded many people purposefully creating unreadable works that are considered beautiful works of art, particularly as it pertains to cursive and calligraphy. However, my interest in marrying asemic writing to musical scores is to take the shapes of the written language of the musical score (durations, the staff, clefs, etc.), break that musical notation into parts, and then re-sequence them into different forms that still appear to be musical, but just foreign enough to traditional musical notation to make it highly interpretive.

In a way, these types of musical scores become performative visual poetry through this type of re-sequencing of the musical vocabulary. The modular interface or instruction in my asemic work is the amalgamation of musical and unmusical gestures that come together in one framework or form. That form then has to be interpreted by a performer based on prior experiences with that shape or gesture in nature or otherwise. Some of these gestures are easier to interpret than others because of the similarities to traditional notation. However, there are vague gestures that have to be worked through a bit more. So far, I’ve categorized these asemic gestures into two types:

Hard – when a visual gesture can be more-easily interpreted into musical phenomena based on how closely related it is to a shape in traditional musical notation. Usually these gestures can be interpreted only a couple of different ways.

Soft – when a visual gesture is much more ambiguous and can be interpreted in more than one musical way. These types of gestures tend to hold more of an important role of the overarching shape of a piece, and could play roles of changing dynamics, tempo, energy and intensity, extended techniques, etc.

The first, successful large-scale piece I produced using this combinatory approach of modularity and asemics is on life, death, and light (2018) for one vocalist and two instrumentalists. In the score, I included some basic instructions on how to approach the work so that musicians new to the experience weren’t too daunted by its openness.

Since the premiere of on life…, many other large-scale pieces and sketches have been produced using this combinatory method, and it’s been a joy to develop the vocabulary for future pieces.