The development of one’s individual, compositional voice is the motivation behind being a curious contemporary composer. Modern composers spend many years developing their craft and musical vocabulary to the end that they can claim a small corner of the musical universe as their own, then share that corner with others. However, the influence of technology and use of certain tools also play an important role in a composer developing their techniques, vocabulary, and craft. Today’s compositional focus tends to center around graphic notation and its development in a composer’s works. Though graphic notation isn’t a new phenomenon (there are examples of graphic notation in the development of Western music notation as early as 840 C. E.), it can be used as a viable solution to represent what can be difficult to notate in traditional music. For example, graphical representations of sound were particularly helpful in the incorporation of synthesizers and fixed media into 20th Century music scores, as those sounds cannot be accurately represented exclusively in a pitch-based, rhythmic-based notation system. Therefore, a visual representation for those types of complex sounds and textures had to be developed. In time, entire pieces were developed in graphical notation, pushing this representation of sound in notated form to a new place for future composers to deeply explore.

With so many tools, apps, online resources, and methods available to modern composers, it can become difficult to navigate which methods and tools are right for helping to develop graphical concrete ideas and the cleanness of one’s graphical notation vocabulary. In this post, I’ll lay out some of my own methods that have helped me to develop my graphical notation language in hopes that it will help other composers to think about their own workflow and future needs.

Methods

A methodical approach to graphical composition is essential for me. There are pathways that I enjoy working in and pathways that I choose to avoid. Overall, a composer should find a balance in what they like working with and take stock in what kinds of those methodical materials makes positive differences in their compositional workflow. Ideally, a composer should be comfortable with their natural workflow but always seek ways to improve it. Below are a few general points to consider. Growing within these points have greatly helped my workflow of creating graphic scores:

It’s important you feel that you’re intentionally crafting something. It seems so simple, but I believe this is one of the most essential parts of being a composer that’s curious about how to improve their graphical notation. Always use materials that will give graphical scores a quality look and feel but are also a joy to work with in the score-making process. Some use watercolor, others use pens… others use rocks. Ultimately, the process and your final product should make you proud. On top of that, it’s important that composers make each marking with careful intentionality. When I sketch or write, I only use pens and markers. Though pencils can be helpful for planning out certain stages, dependence on the pencil at all stages of composition makes me rely too much upon markings being erasable. This practice will also help you to physically get used to the medium that your final product will be etched in.

It’s important that you have the proper materials and workspace to work as efficiently and creatively as you can. I have found that much of the reason composers have trouble producing quality graphical scores is because they aren’t working with materials or working within spaces that they’re comfortable with. From what I’ve learned in studying the workspaces of historical composers, authors, and visual artists, a thoughtfully-designed workspace certainly helped them to produce their works in an intentionally personal fashion. In an Artists Magazine article highlighting the special workspace of Henri Matisse, we see that he surrounded himself with meaningful artifacts from all over the world:

Throughout his career, Matisse acquired a variety of objects that would serve as creative inspiration, as reminders of past experiences and as guides to the pictorial languages and formal devices of other cultures. They range from humble household items, like a tobacco jar, to more exotic objects such as Oceanic masks and Tahitian textiles.

Artists Magazine

Many of these artifacts appear multiple times in his paintings. They take on a variety of roles, almost as a repertory actor might take center stage for one performance and appear as a minor character in the next.

Like actors, the objects mutate in his work, their proportions and color transformed by the new relationships and settings in which they find themselves. When they weren’t being used as subject matter, they took their places as part of the ever-shifting domestic environment Matisse needed to sustain his imaginative world.

Matisse found the inspiration that he needed by being surrounded by objects from all over the world. This is what he needed to intentionally cultivate a certain kind of curiosity that’s saturated in his work. We aren’t all a Matisse, but we can take some advice from how he designed his workspace. It’s important to designate or design an area of the house, studio, apartment, etc. specially to do compositional work in. This should be a place you enjoy working in, with materials that compel you to get straight to work – however minimal or colorful that space may be. This space could be anything from place that displays artifacts, paintings, books, a drafting table, etc. to a place that’s as minimal as it gets. Carefully and thoughtfully explore your own personality and preferences, and don’t settle for a workspace that you constantly avoid. My own workspace contains a couch, coffee table, bookshelves, art, musical instruments from around the world, and a drafting table as its central focus. At first, you might feel as if you’re logging in practice hours, but – if you keep at it – you’ll find that time passes by without notice. You might also find that your decorative influences help you in your notation process and etching your graphical vocabulary.

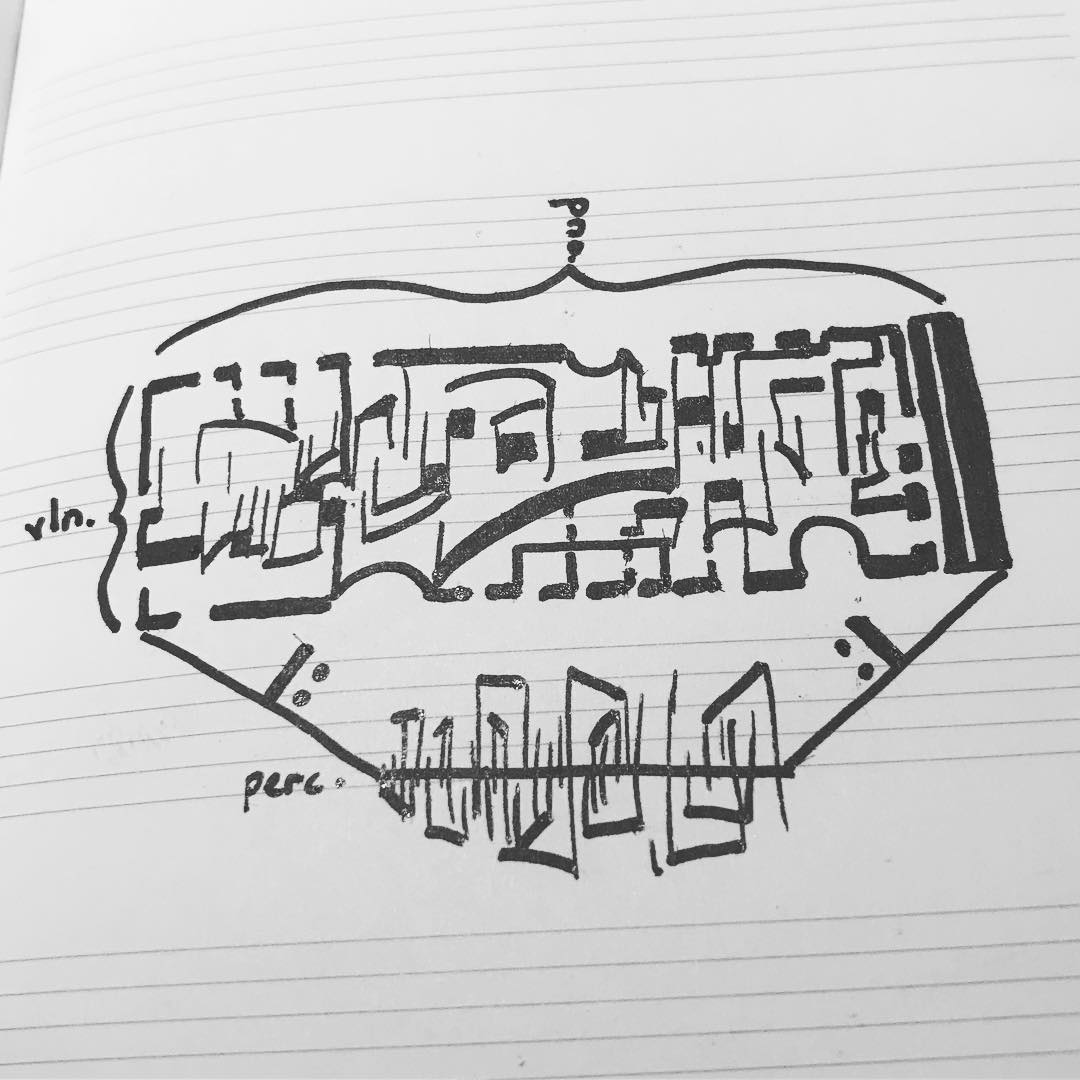

It’s important that you spend time composing and sketching every day. Build the skills that you need to succeed, and put those skills to the test every day. Not every sketch you come up with will become a profound piece of music. In fact, many of my sketches are used to study a certain musical gesture and nothing more. With that said, play the long game; think of your sketching time as a stepping stone to or part of a future piece. Many composers kept a notebook with them that catalogued themes and forms for later use. It’s a great, quick way to jot ideas down with the intention that you can tease them out later. Keep the notebook on you and start cataloguing as soon as you get an idea. Don’t wait to put it into a notation etching program. Sketch when you go on walks or if you have a spare moment before a meeting. Carry your sketchbook with you and capture the inspiration found in every day situations by sketching gestures and musical devices. Soon, you’ll build a vocabulary that you can use however you want, and your skills will improve.

It’s important to study and listen to the graphic scores of other composers – historical and contemporary. One of the best parts about studying and crafting graphic scores is discovering the variety of personalities each work can have. Every composer has a different approach to graphic scores and how to represent certain musical phenomena. I’ve found that learning the graphic musical language is a lot like jazz improvisation: you can teach yourself drills, riffs, and patterns all day, but – in the end – jazz musicians need to supplement that practice with listening to and imitating the masters of the craft. They carry the tradition of the masters and incorporate it into their own playing, all while doing something new and innovative with that knowledge. Learn that vocabulary and assimilate it into your own works. If a gesture from their score is effective, use it. Then, sketch upon it further to give it new life in the body of works that you create. It also helps to join a social online forum of composers and musicians that like sharing their ideas about graphic notation. You can also subscribe to a variety of Youtube channels that regularly post scores with audio. These are just a few ways that you can get started seeing what composers have done or are doing to further the graphical vocabulary of music.

Search for What Personally Inspires You. There is so much to discover in this world, much less the musical world. With all this inspiration and all the works that have been done in the light of that inspiration, there is still only one of you in the world. Each modern composer strikes a unique balance of ideas and views from life experiences and shows that balance in their own, unique works. Your graphical ideas reflect the personal balance that you have; the ideas and views that make you unique to the world. It could be your knowledge of a certain instrument and how specific techniques can be graphically notated. It could be your love of nature and how you want to best represent the physical shapes that you see and translate them into musical information. The main idea is: be honest with yourself about your passion, and follow the musical path that you want to explore most. That path may not be as paved as some of the other composers’ paths, but working on that proverbial pavement is what the art of composition is all about. Accept constructive criticism as helpful with the mindset that your art is constantly to be improved upon, and that only you can diligently practice to improve it.